A Girl Called Easter: Unusual Name for a Spring Baby

Easter Brumley Vanlandingham Kimbley: 1782-1847 (Maternal Third Great-Grandaunt)

Easter Brumley Vanlandingham was given a striking, unusual

first name—a name that was often misspelled and misrecorded as “Esther” on

documents and records. Her name begins with two vowels (corresponding with this

week’s prompt), and evokes positive energy that seems to promise new beginnings.

Easter Vanlandingham was born April 30, 1782 in St. Stephen

South Parish in Northumberland, Virginia. According to my research, the holiday

of Easter fell on March 31 that year. Did her parents, Ezekiel Vanlandingham

and Elisabeth Oliver Brumley, name her Easter due to her spring birth date,

just 4 weeks after Easter Sunday? Had they perhaps expected her to be born on

Easter, and were surprised that she didn’t arrive when expected? Did they

choose the name as a reminder of the Easter story’s message of rebirth and

renewal? We will never know.

Easter appears to be the oldest of their three children. I

have found no primary source materials that provide Ezekiel and Elizabeth’s wedding

date; some secondary sources gave a marriage date for the fall following

Easter’s birth, which is incorrect. The record of her birth is contained in

Virginia Colonial Abstracts, and lists her parents as husband and wife.

Easter’s siblings, Oliver Cromwell and Elizabeth Vanlandingham, were born in

1785 and 1788.

In 1796, the Vanlandinghams joined a group of pioneers

headed for the newly opened Kentucky territory. Ezekiel died during the

journey, leaving his wife and three children to continue to Kentucky without

him. A history of Muhlenberg County,

Kentucky reported that:

“After burying her

husband Mrs. Vanlandingham and the other members of the party resumed their

trip and finally arrived near Paradise where she procured some land. There she

and her…children worked hard and soon placed themselves in comfortable

circumstances. She was a well-educated woman, and up to about the time her

children were married devoted practically all her evenings to their education.”

Easter was 14 when she arrived in Kentucky. Her youngest

sister was only 8, so Easter probably helped to care for her. In addition, her

mother remarried and had other children. Easter was probably a vital member of

the household, providing support for her mother.

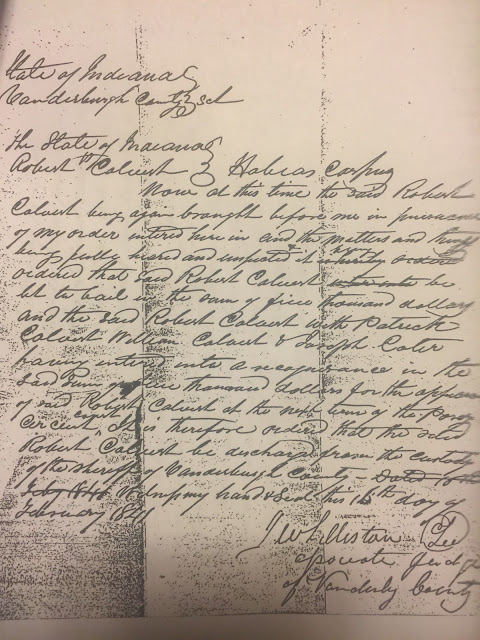

This probably explains Easter’s late marriage. She was 30

years old when she married Francis Kimbley on February 14, 1813. He was only twenty at the time of the

marriage, so she was a full decade older than him! Some later documents shave a

few years off her age—she probably didn’t want to admit how much older she was!

Her younger sister, Elizabeth, married the same year.

Francis Kimbley was a farmer and slaveowner. His property

was mostly in Ohio County, Kentucky, but Easter and Francis’s children were

born both in Ohio County and neighboring Muhlenberg County, so I expect the

Kimbleys had property in both counties.

Easter gave birth to their first son, Oliver Christopher Vanlandingham

Kimbley (named for Easter’s brother) on December 23, 1813—ten months after their

marriage. Daughter Elizabeth was born two years later, followed by sons Ezekiel

Vanlandingham Kimbley in 1817, Andrew Jackson Kimbley in 1819, Francis Edward

Kimbley in 1822, and John Franklin Kimbley in 1823.

Easter died on Christmas Day, 1847 at the age 65. She was

buried in Nellie Davis Cemetery in Ohio County, Kentucky. Her husband Francis

lived another fourteen years, dying in 1861 at age 70.

Easter’s children went on to raise families of their own in the Ohio and Muhlenberg County area. The 1860 census shows son Ezekiel, his wife and three children living next to Francis, and son Andrew Jackson Kimbley, his wife and three children farming on the other side of Francis’ property.

|

| Son Francis Kimbley a few farms from brother and father--1860 Census |

|

| Ezekiel Kimbley family, and father Francis on the 1860 census |

Two

properties away was the farm of Oliver Kimbley’s widow Elizabeth and their four

children. A few farms away, son Francis

lived with his wife and children.

|

| Andrew Kimbley family at top, Oliver's widow Elizabeth Kimbley and family below |

Interestingly, Easter’s only daughter, Elizabeth, married

John Everett Vaught Smith, brother of second-great-grandfather Elijah Smith, so

the two ancestral lines crossed. Elizabeth and John had several children and

lived in neighboring Mclean County, Kentucky.

Easter’s final child was the most well-known, and the only

one who didn’t go into farming. John Franklin Kimbley became a doctor, and he served

as a Union physician during the Civil War. He returned to Owensboro, Kentucky

following the war to practice medicine. He married Sarah Lucetta Ray, the

daughter of Indiana Governor James Ray. The couple had two children.

Easter’s name was carried on to the next generation. Easter’s daughter named one of her children Easter, but the name was often misspelled as Esther—even her headstone reads “Esther Smith Kirtley”.

|

| Easter Smith Kirtley misspelled as Esther |

Son Ezekiel gave his daughter

Susan the middle name Easter. Son Francis Kimbley named his eldest daughter

Easter Ann in honor of his mother.

I wonder how these women felt about sharing a name with a

religious holiday. I love the name, and enjoyed writing about Easter

Vanlandingham Kimbley just in time for Easter 2023. Easter is a name rich both in

vowels and in meaning.

Sources:

Abstract of Birth Record from “Virginia Colonial Abstracts. https://www.ancestry.com/discoveryui-content/view/340765:48429?tid=81812584&pid=262448858851&hid=1037581386036&_phsrc=Jng22546&_phstart=default

A History of

Muhlenberg County by Otto A. Rothert. John P. Morton & Company.

Louisville, KY 1913. Accessed through Google Books

.jpg)

.jpg)