The Unconventional Wilkins Siblings: Three Brothers, Three Tragedies, and One Lone Sister

Richard R. Wilkins: 1831-1852 (Maternal Second Cousin 3x

Removed)

Samuel M. Wilkins: 1839-1915 (Maternal Second Cousin 3x

Removed)

Edward Wilkins: 1840-1901 (Maternal Second Cousin 3x

Removed)

Eliza Wilkins: 1842-1913 (Maternal Second Cousin 3x Removed)

I was intrigued when I ran across the Wilkins family while studying

the descendants of the Weir family. Richard, Samuel, Edward and Eliza Wilkins

were the children of James Weir Wilkins and Elizabeth Poag. The four siblings

seem to have had all the advantages. Their father was a farmer, merchant and school

commissioner and seems to have provided the family with a comfortable living. The

family seems to have been well-liked; James Wilkins was known locally as Uncle

Jim according to one news item I found. Yet all three brothers never married or

fathered children, and all met tragic ends. The lone daughter, Eliza, also

never married, devoting all her energy to her local church and charitable

works. What caused these siblings to choose their unconventional paths?

Richard Wilkins is perhaps the most mysterious of the four

siblings due to the lack of information about him. He was the eldest of the

Wilkins children, born around 1831. He appears on the 1850 census along with

his parents and siblings. He is listed as being 19 years of age, and the

occupation entry lists him as “at

school”. This seems odd; he was too old to still be in high school. Perhaps he

was attending college, although I have found no records to confirm this

hypothesis.

Just two years later, his death appears in the Kentucky state death records. It is an interesting entry. It states that Richard was a single male, age 21, and was born in Madisonville, Kenturcky to James and Eliza Wilkins. This is all routine and expected. However, while all the other deaths reported on the page took place in Kentucky, Richard’s entry states that he died June 1, 1852 “near Fort Kearney Nebraska”. Cause of death is listed as “cholera” and a further notation states that Richard was “en route to California”.

|

| Richard Wilkins death record |

So Richard had left home, perhaps to seek his fortune in the

goldfields of California as the 49ers gold rush had begun just three years

earlier. Curiously, the local newspaper did not run an obituary or death notice

for him, or any articles announcing his decision to move west, despite the

family’s prominence in the community. Richard was not buried with the family

either; he must have been buried in Nebraska. Why was his death ignored by his

family and community?

Second son Samuel Wilkins was born in 1839, and appears on

census records in 1860, 1870 and 1880 living with his parents and siblings. As

for occupation, Samuel is listed as a “laborer” in 1870 and a scribble that

might read “wagoner” in 1860. However, by 1880, at age 41, the census shows he

was unemployed, as were his aged father and his remaining siblings. Perhaps Samuel’s

loss of employment marked the beginning of mental illness. Samuel died at age

76 on September 25, 1915 from a cerebral hemorrhage while he was a resident at

Western State Hospital in Hopkinsville, an institution for the mentally ill.

The newspaper notice stated that he had been a patient for twenty years,

meaning he was institutionalized around 1895, about a decade after his father’s

death.

The final son, Edward, was born in March of 1840. He seems to have never held a job or did any kind of work, but lived off his father’s earnings. Even his Civil War draft record lists “nothing” as his occupation.

|

| Edward's Civil War draft record |

The

only census where he lists an occupation was the 1900 census, taken when he was

already sixty years old. He claimed he was a “capitalist”, which sounds a

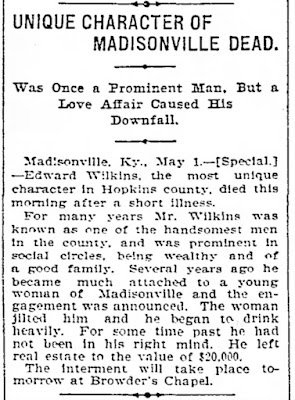

little smart-alecky to me. He died at age 61 in Madisonville, Kentucky. The

obituary was very interesting, calling him “the most unique character in

Hopkins County”. I suspect this was not a compliment. He was described as being

“known as one of the handsomest men in the county, and was prominent in social

circles, being wealthy and of a good family.”

The article went on to describe how he fell in love and

became engaged to a local girl, but she jilted him. “He began to drink heavily.

For some time past he had not been in his right mind. He left real estate to

the value of $20,000.” Perhaps, like his brother Samuel, Edward suffered from

mental illness.

As for the final child, daughter Eliza Wilkins, she never

married and never worked, living with her father until his death in 1885, and

then living at a home on Sugg and Seminary Streets in Madisonville. The

obituary in the local paper described her as a Presbyterian who was “a worker

in the church much of the time. When the end came she was ready as indicated by

her conversation with friends during her last illness. She did many acts of

charity unpretentiously, and had great love for animals, especially those

crippled or mistreated.” Another newspaper said she lived “a long and useful

life”.

From the description, I surmise that she was very religious

and may have been a cat lady or the canine equivalent—at the very least, she

was a little eccentric.

So all four of James Weir Wilkins and Elizabeth Poag’s

children seem to have struggled to fit into their community. James supported

his children for his entire life. Once he died, they seem to have floundered, having failed to launch careers and families of their own. Despite the Wilkins family’s

prominence in the town of Madisonville, Kentucky, it appears the Wilkins

children were troubled. James Weir Wilkins and his wife Elizabeth Poag were

first cousins—their mothers were sisters. Could this close genetic relationship

have been part of the problem? Did mental illness run in the family? The

Wilkins siblings leave me with many unanswerable questions.

Sources:

1850, 1860, 1870 and 1880 United States Census.

Ancestry.com. https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/7667/records/39425881?tid=81812584&pid=262650250655&ssrc=pt

Kentucky, U.S., Death Records, 1852-1965. Ancestry.com https://www.ancestry.com/search/collections/1222/records/307132?tid=81812584&pid=262650328964&ssrc=pt

“Four Deaths at Hospital”. Hopkinsville Kentuckian.

Hopkinsville, KY. September 28, 1915. Newspapers.com.

U.S., Civil War Draft Registrations Records, 1863-1865.

Kentucky. Snd. Class 1. Ancestry.com

“Unique Character of Madisonville Dead.” Courier-Journal.

Louisville, KY. May 2, 1901. Newspapers.com.

.jpg)