Fire, Smoke and Soot:

Life in the City of Coatbridge/Airdrie, Scotland

John Sutherland 1813-1892

Bethia Muir: 1815-1894

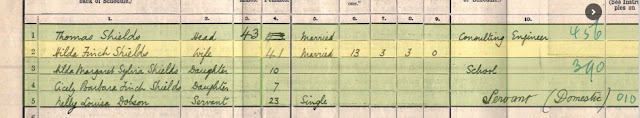

Margaret Sutherland Shields, Bruce’s second great

grandmother, was born May 25, 1837 in the town of Coatbridge in Lanarkshire,

Scotland. Her parents, John Sutherland and his wife Bethia Muir Sutherland, had

grown up in the area. The years after Margaret’s birth saw dramatic changes in

both the city of Coatbridge and in her parents’ circumstances.

John Sutherland came from humble beginnings and moved up in

the world through hard, brutal work in the Coatbridge area. According to

information John Sutherland provided on census records, he was born around 1812

or 1813 in either Barony, Old Monkland or Rutherglen, all towns or parishes in Lanarkshire

near Glasgow. His father, John Sutherland, was a coalminer. His mother was

Annie Jean Smith. He had several siblings.

|

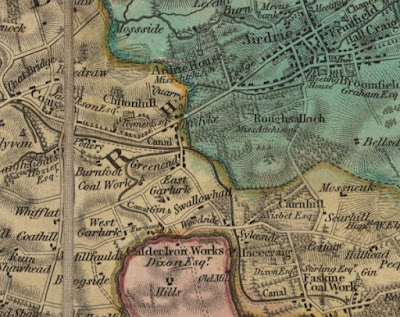

| Old Monkland Parish, 1816 |

John married Bethia Muir in June, 1834. She was the daughter

of Robert Muir and Margaret Anderson Lauder of Old Monkland. She was born

October 29, 1815; the birth record states that at the time, her father was

working as a weaver.

John Sutherland had followed his father into the mines. The

1841 census lists him as a coal miner, with the family, now including two

children, John, 6, and Ann, 2, (Margaret’s whereabouts are unknown. She would

have been age 4) living at “Allan’s Place, Langlone” in the Old Monkland

parish.

According to the 1851 census, John Sutherland had completely

changed careers at some point during the 1840s. In 1851, he supposedly was

working as a bookseller—quite a contrast to coal mining. The family, now with

six surviving children, was living on Church Street in Old Monkland. I have

some doubts about the accuracy of his occupation—could this be a transcription

error?-- but the family seems to be moving up in the world a bit.

By 1861, the family’s fortunes were definitely improving.

They now lived in a home with a name—The Old Manse in New Monkland, and John’s

new occupation was “ironstone centresictor”. I have no idea what a

“centresictor” might be, nor does Google or the dictionary. I suspect this is a

transcription error—perhaps ironstone contractor? I suspect he was brokering

the sale of iron ore to foundries for processing.

I was able to track down photos of the Old Manse. There were

two homes by that name, both quite large and grand for the area. The first was

torn down around 1870 or shortly thereafter, so I believe the photo of this

original home shows the building the Sutherlands called home in 1861, the year

Margaret married Thomas Shields.

By 1871, the family had relocated to a home at 60 WellWynd

in Airdrie, and John Sutherland was listed as an “iron forge master”, which

could indicate he was the owner of the business or at least a manager. According

to Ruth McNiven her grandmother Margaret’s family owned a foundry in the town

of Airdrie, and were quite wealthy. She said the Shields boys could ride their

bicycles around the Sutherland billiard room. As the 1871 census shows Margaret

and Thomas Shields and their five young children also living at 60 WellWynd,

the Shields boys would have had many opportunities to ride around there.

|

| 1858 Airdrie Ordnance Survey Map showing Wellwynd and the Airdrie Foundry |

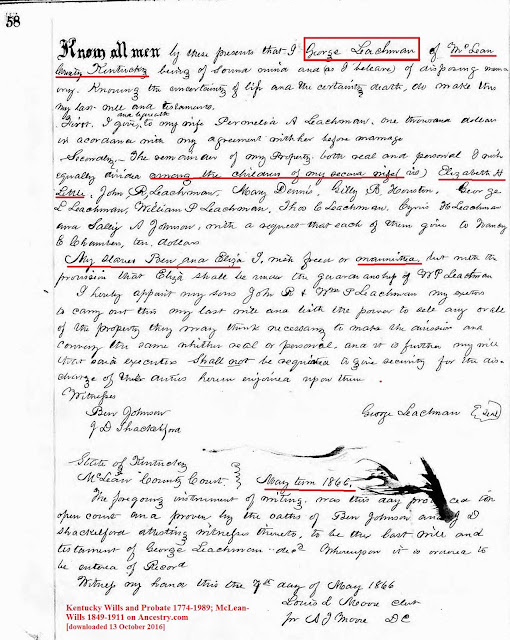

I have tried to find information about the foundry. Histories of the area describe several foundries in and around Airdrie, but the Sutherland name has not turned up in connection with any of them. However, another Ancestry tree that includes the Sutherlands connected the Airdrie Iron Foundry to them, posting the following document, which I believe was a stock share of some sort.

Note that the document has an address, 72 WellWynd, printed

at the top. Interestingly, this is just down the street from the Sutherland

house. It would make sense that John would live near his business. In addition,

the document references a Smith family member. As I mentioned earlier, John

Sutherland’s mother was a Smith. Perhaps he was related to the foundry’s owner

or previous owner.

An ordnance gazetteer from 1885 has an entry for the Airdrie

Iron Foundry, stating it was owned by David Smith. As I have been unable to

identify Annie Jean Smith Sutherland’s extended family, I don’t know if David

Smith is a relative or not. He may have purchased the foundry from the

Sutherlands, as John Sutherland was retired by that point.

|

| Ordnance Gazetteer entry for Airdrie Iron Foundry |

So what was this area of Lanarkshire like in the mid to late

1800s? Airdrie lies just outside the larger town of Coatbridge, and both

communities were only ten miles from Glasgow, with Old and New Monkland in

their midst. The entire area is now part of the greater Glasgow metro area, but

in the mid-1800s, they were all still separate communities. Here is a

description of Coatbridge in 1846 by Samuel Lewis:

“Coatbridge, a village, in the late quoad sacra parish of

Gartsherrie, parish of Old Monkland, Middle ward of county Lanark, l 1/2 mile

(NW) from Airdrie, containing 1599 inhabitants. This is a very thriving place,

which has more than doubled in extent and population within the last fifteen

years, owing to the extension of the iron trade in the district, and to its

being in the vicinity of valuable coal-mines; the Dundyvan and Summerlee

iron-works in the neighbourhood are conducted on a large scale, and afford

employment to a great part of the population. The village is on the road from

Airdrie to Glasgow; and the Monkland canal also affords facilities of

communication with the adjacent towns. A post-office has been established here,

and there is a place of worship for members of the Free Church.”

Here is his description of neighboring Gartsherrie, where

the Shields boys attended the Academy:

“Gartsherrie, 2 miles W from Airdrie… is a considerable

mining district, in the works connected with which the chief of the population

are employed: the ironworks are of great magnitude, and include a number of

blast-furnaces for the smelting of the ore. The coal-mine here is also worked

on a very extensive scale; there are five strata of coal, between each of which

is a stratum of sandstone and shale : the seams of coal vary in thickness from one

foot four inches to four feet. The Glasgow and Garnkirk railway, which starts

from St. Rollox, in the north-east quarter of the city, joins the Monkland and

Kirkintilloch railway at this place. …The church, erected at a cost of £3300,

is an elegant structure, with a tower rising to the height of 136 feet, and

contains 1500 sittings. Near it is the Academy, erected in 1844, at cost of

£2300; and there is a large Sabbath school in connexion with the Establishment.”

From these descriptions we can tell the area had grown

quickly due to the coal mining and iron foundry businesses, but the area still

had fewer than 10,000 inhabitants. However, for the time period, it qualified

as a city. The size of the church alone attests to that—seating for 1500

people! Wow!

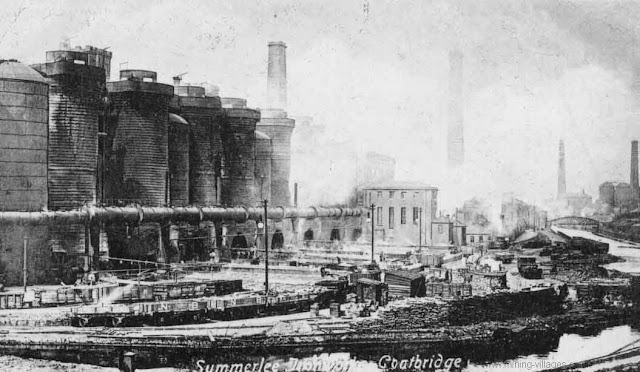

As the mining and iron foundry businesses grew, there were impacts on the towns. During the last decades of the 19th century, Airdrie and Coatbridge/New Monkland were hardly garden spots. Here is a description from the 1880s by Francis Groome:

“The Airdrie and Coatbridge district comprises 21 active collieries; and in or about the town are 5 establishments for the pig-iron manufacture—Calder, Carnbroe, Gartsherrie, Langloan, and Summerlee—of whose 41 furnaces 29 were in blast in 1879, when 8 malleable iron-works had 113 puddling furnaces and 19 rolling mills.

“Coatbridge,

in its growth, has absorbed, or is still absorbing, a number of outlying

suburbs-Langloan, Gartsherrie, High Sunnyside, Coats, Clifton, Drumpellier,

Dundyvan, Summerlee, Whifflet, Coatdyke, etc.; and the appearance of the whole,

redeemed though it is by some good architectural features, is far more curious

than pleasing. Fire, smoke, and soot, with the roar and rattle of machinery,

are its leading characteristics; the flames of its furnaces cast on the

midnight sky a glow as if of some vast conflagration.”

Summerlee Iron Works with Gartsherrie Burn at left foreground (stream) and Monkland Canal at the right

Another writer describes the town as follows:

"Though Coatbridge is a most interesting seat of industry, it is anything but beautiful. Dense clouds of smoke roll over it incessantly, and impart to all the buildings a peculiarly dingy aspect. A coat of black dust overlies everything, and in a few hours the visitor finds his complexion considerably deteriorated by the flakes of soot which fill the air, and settle on his face.”

The writer goes on to describe the night sky lit with a

“lurid glow” by the fires of over 50 blast furnaces belching “great tongues of

fire”.

|

| Summerlee Iron Works Coatbridge, with smoky sky |

Findlay notes in his History of the Iron and Steel Industry

in Scotland:

“The iron industry peaked by about 1871, at which time it

employed nearly 40% of the Scottish workforce, and 25% of its steam power. In

Coatbridge the ground vibrated from the pounding of steam hammers and a forest

of chimneys spewed soot and grit across Coatbridge, which had become the most

polluted town in the UK, if not the World. At times it turned day into a night,

lit by the blast from the furnaces.”

No matter the size of the Sutherland billiard room during

the family’s most prosperous times, the noise, water and air pollution must

have made life difficult. It is hard to imagine raising small children in such

an environment, especially when the Sutherlands and Shields families lived just

a few steps down the street from one of those fire and smoke belching

foundries. While they had come up in the world, they were paying a price for

their success.

|

| Anderson St. in Airdrie, near the 60 WellWynd house owned by Sutherlands |

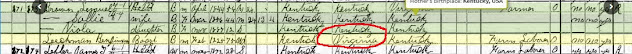

Perhaps this is why, by the time of the 1881 census, the

Sutherlands had moved back to New Monkland, where they were living in the more

modestly named “Muirshill Cottage.” John Sutherland’s wife was born a Muir, so

perhaps they lived in a Muir-owned property. John was now listed as a

“portioner”, which I assume is similar to “pensioner”. He was 68 years old, so

was no longer working.

A few years later, the Sutherlands had moved back into

Airdrie. The 1891 census finds them living at 2 Inglefield Terrace in Airdrie.

John is listed as an 80 year old “retired iron forger”. It appears his second

son, William, had taken over the foundry and the house at 60 Wellwynd.

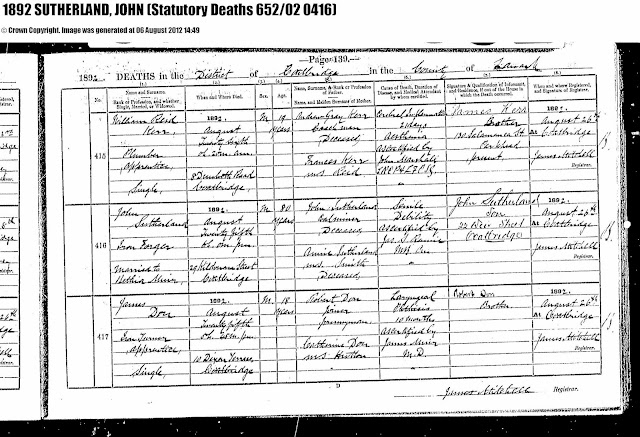

John Sutherland died August 25, 1892 at age 79 or 80. His

wife Bethia died April 3, 1894. The iron and coal industries in Scotland and

the Coatbridge area went into decline as other areas of Great Britain became

more dominant. The skies above Coatbridge and Airdrie are far cleaner today.

Sources:

Ordnance

Gazetteer of Scotland, Francis H Groome, 1885

http://www.scottishmining.co.uk/34.html

Article titled “History of the Iron and Steel Industry in

Scotland” by C. Findlay. Scottish Steelworks History website: https://cfindlay17.wixsite.com/clydebridge/history-of-iron-and-steel-in-scotla

National Library of Scotland ordnance survey maps. https://maps.nls.uk/townplans/coatbridge.html