Too Little Too Late: Leachman Slaves Freed Months After Civil War’s End

George Leachman: 1794-1866

After President Biden made Juneteenth a federal holiday last

month, Americans are being forced to finally recognize that the Emancipation

Proclamation, enacted on January 1, 1862, wasn’t an immediate Get Out of

Slavery Free card. Actual implementation of Lincoln’s proclamation relied on

Union Army enforcement. That didn’t come for months or even years to large parts

of the Confederacy. Now with the new holiday, people believe that slavery’s end

came on June 19, 1865—Juneteenth-- when Union forces publicized the act in

Texas following the end of the war. However, there were regions where freedom

came even later than Juneteenth. I didn’t discover this until I found the will

and probate records for Bruce’s third-great-grandfather George Leachman.

George Leachman appears to have been born in Prince William

County, Virginia, to parents Sampson Leachman and Nancy Ann Davis. All of

George’s siblings were born in Kentucky, so it appears Nancy had returned to

Virginia briefly before giving birth to George, perhaps on a visit to family

members--she too was born in Prince William County. She returned to Kentucky,

however, and George grew up near Atoka in Boyle County, Kentucky. (Note: there

are errors in this section of tree regarding George’s siblings that must be

investigated.)

After a brief youthful marriage that ended with the death of

his wife Polly Crow Leachman in 1817, George married Mathilda Robertson on

October 28, 1819. George and Mathilda had ten children over the course of thirty

years of marriage. Mathilda died April 23, 1849 giving birth to their tenth

child, Samuel Leachman. Little Samuel lived for ten months after Mathilda’s

death before he too died in February of 1850.

George remarried for a third time on December 4, 1856 when

he was 62 years old. His bride was Permelia Murray Davis, a widow of about 46

years old. They had no children.

While George and his family apparently lived on the same

farm from 1819 onward, the federal census moves him from Daviess County to

McLean County, beginning with the 1860 census. Wikipedia helped to explain this

discrepancy. In 1854, Daviess County ceded some land to McLean; apparently the

Leachman property was part of the land ceded to McLean County. The 1840 census

listed the farm as part of the community of Panther Creek; later census forms

stated the post office used by the rural residents was in Calhoun, Kentucky.

These two communities are about ten miles apart to the southwest of Owensboro.

Presumably the Leachman farm lay somewhere between the two towns.

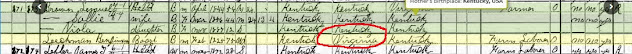

The 1840 census did not identify individuals by name other

than the head of household. Family members were only distinguished by category—age,

sex, and whether they were free or enslaved. That is how I first discovered

that George Leachman owned two slaves.

The next two censuses in 1850 and 1860 included separate

Slave Schedules, where the homeowner identified the slaves by age and sex.

George had fewer slaves than most of his neighbors—three neighbors had 14, 15

and 20 slaves respectively, and several others had four to six. George’s two

slaves in 1850 are listed as a 47 year old woman, and the other a 27 year old

man.

In 1860, George still owns the same two people, now listed

as being 55 and 33. It is unclear which set of ages was incorrect, or if George

really knew how old these people were. It is interesting to note that some of

the Leachmans’ neighbors had acquired more slaves between 1850 and 1860—William

Johnson started with four slaves, and by 1860 had 22. Other families no longer

appear on the schedule—did they leave, or sell their slaves? Many of the slaves

listed on the schedules were children—Kentucky had outlawed the importation of

new slaves from out of state, so growing numbers of slaves often reflected the

formation of slave families on the farms and plantations.

George was too old to fight in the Civil War when it broke

out in April 1861. However, the war apparently came to him. A battle was fought

at Panther Creek on September 19, 1862. The Confederate Army had taken the town

of Owensboro, and Union forces from neighboring Indiana crossed the river and

attacked them. Despite being outnumbered nearly two-to-one, the Union forces

prevailed and drove the Confederates back. I’m sure the Leachman family could

hear the battle raging; they were at most five to ten miles away.

George died just thirteen months after the Civil War ended.

He died at age 71 on May 2, 1866, and was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in

McLean County.

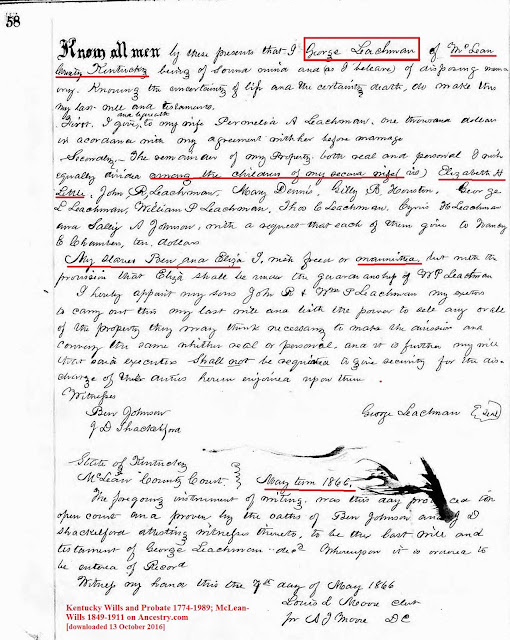

George’s will was probated May 4, 1866. The provisions

included $1000 to his widow Permilia “in accordance with my agreement with her

before marriage”, with the remainder of his property divided equally between

his nine surviving children; each child was identified by name in the will.

The will’s final provision was the shocker. “My slaves Eliza

and Ben I wish freed or manumitted, but with the provision that Eliza shall be

under the guardianship of W.P. Leachman.”

How can this be? The will was probated in 1866, a year after

the end of the Civil War and four years after the Emancipation Proclamation.

How could George still own slaves? Did he actually

still own slaves at the date of his death, or was the will just written years

earlier and never updated to reflect their free status?

I started researching, and was shocked to discover that in

the slave states of Delaware and Kentucky, the Emancipation Proclamation hadn’t

applied to slaves held there. The Proclamation was only directed against states

that seceded from the Union. Delaware and Kentucky never seceded, so their

slaves were not freed by Lincoln’s proclamation!

As Tim Talbot noted in his paper cited below, “…slavery only

truly ended in Kentucky with the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which

the state chose not to ratify.”

The 13th Amendment wasn’t ratified until December

6, 1865, months after the end of the war, and since Kentucky refused to ratify

the Amendment, it is hard to say exactly when the remaining slaveholders in the

state actually freed their slaves. So it is possible that poor Eliza and Ben

were still working involuntarily for the Leachmans when George died. However it

is equally possible that they had been freed either at the end of the war or in

December 1865.

At least George had planned for Ben and Eliza’s freedom at

his death and hadn’t intended to pass them on to his children along with the

furniture, land and livestock.

I don’t know if Eliza and Ben were mother and son or

unrelated, and I am not sure what surname they chose to use following their

emancipation. I wonder if Eliza really remained under the “guardianship” of W.

P. Leachman, or if she preferred to make her own way in the world. She was not

a member of William Parker Leachman’s household on the 1870 census, but that

could mean she had died. Since George felt she needed protection, Eliza may

have been in poor health.

As for Ben, I found a mulatto farmer named Ben Leachman on

the 1870 census living with another black family in McLean County. The age

listed, 42, would be close to the right age for the Leachman’s slave Ben. Since

Ben Leachman is listed on the 1870 census record as a mulatto, it occurred to

me that George Leachman might actually have been Ben’s natural father as well

as his owner. I found a black man named Benjamin Leechman on the 1900 census—a widower

born in 1825 in Kentucky to a father born in Virginia—that would fit with

George Leachman, born in Virginia, being his father, and the slave Eliza his

mother. However, these details, while suggestive, are not proof of any parental

relationship.

|

| 1870 census |

I hope Ben and Eliza had a good life wherever they ended up,

but sadly, freedom often meant a life of poverty and difficulty for former

slaves.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daviess_County,_Kentucky

https://civilwartalk.com/threads/battle-at-panther-creek-kentucky.146816/

Battle at Panther Creek Kentucky. By Taylin.

Tim Talbott, “Slavery Laws in Old Kentucky,”

ExploreKYHistory, accessed July 3, 2021, https://explorekyhistory.ky.gov/items/show/180

No comments:

Post a Comment