A Young Man’s Struggles: Beverly Childress Faces Setbacks

Beverly John Childress: 1903-1969 (Maternal Third Cousin 2x Removed)

Beverly

John Childress’ early life seemed to be nothing but “hard times”. He lost a

parent at a tender age, was separated from his siblings and sent to stay with

relatives, and just as he neared adulthood, he suffered a grisly on-the-job

accident that left him seriously injured and could have killed him. Despite

these hard times, he survived and managed to raise a family and pursue a career

that brought him satisfaction.

Beverly

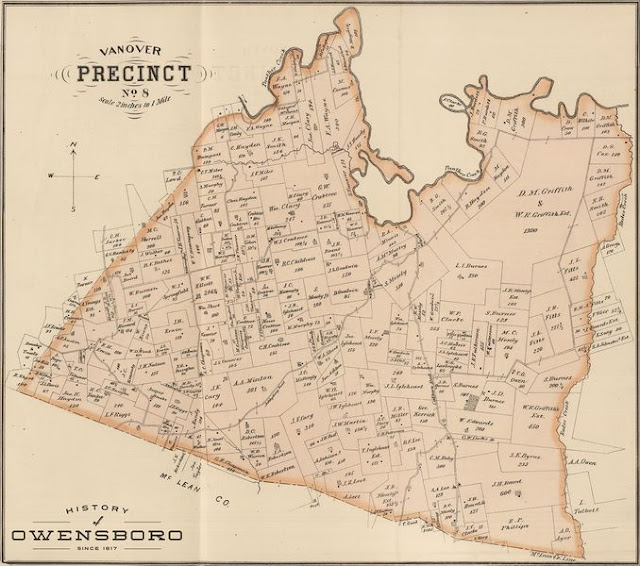

John Childress was born in Daviess County, Kentucky on August 10, 1903 to

parents Fisher Alexander Childress and Lydia Moseley Childress. He was the

third of their five children, and was named after his grandfather Beverly

Childress..

Tragically, Beverly’s mother Lydia died at age 39 when Beverly was only eight years old. According to Lydia’s obituary, she “died of a complication of diseases…after a long illness.” Beverly’s father, a farmer, tried to keep the family together after his wife’s death. However, at times this must have been difficult. Even before Lydia’s death, little Beverly was living with his grandparents, John Presley and Luvenia Moseley, as seen on the 1910 census form below.

John

Presley Moseley apparently stepped up financially as his 1920 will indicates:

“I have

five grandchildren by my deceased daughter Lydia Childress, viz: Goble

Childress, Virgie Childress, Beverly Childress, Richard Childress and Ollie

Childress, and having already done much for these grandchildren and hoping to

do more for them during my lifetime, I do not devise my said grandchildren

anything at all, but I do entrust the welfare of said grandchildren to my wife,

Luvenia Moseley, and if at the time of my death or at any time thereafter…she

desires to give any of my…estate or forward property to any of said

grandchildren, it is my will and desire that she do so as I have full

confidence in my wife…and feel that she will do what is just, right and proper

for said children.”

In February

1920, when Beverly was only sixteen years old, he married a fifteen year old

named Lucy Jane Kirk. Her brother was the county attorney at the time. The

young couple’s first child wasn’t born until December 1920, so it doesn’t

appear it was a shotgun wedding. However, they were very young to be married,

and must have struggled. Neither completed high school.

To support

his wife, Beverly took a job at the Kentucky and Virginia Tobacco Company in

Owensboro. His job involved “prizing” the tobacco, which meant to press or pack

down the tobacco into hogsheads, which were huge barrels. An article from the

North Carolina Museum of History cited below describes the barrels as follows:

“These

barrels consisted of red or white oak staves (the long, vertical parts) and oak

hoops, and they usually measured forty-eight inches in length and thirty inches

in diameter at the head. After sale at a warehouse, leaf tobacco got pressed,

or “prized,” into the hogshead. When full of leaf tobacco, hogsheads weighed

about one thousand pounds each.”

Workers screwing down a pressing plate onto the tobacco in the hogshead.

Illustrations

of the hogsheads and pressing apparatus are seen above and below. The tobacco was placed in

the hogshead and then a large metal plate was lowered onto the tobacco and was

pressed or screwed down to tightly pack the tobacco leaves in the hogshead.

This process would be repeated until the hogshead was full of pressed tobacco,

which was then stored for curing and shipping.

1920s image of prizing tobacco--at right you can see the heavy metal plate above the hogshead, similar to what fell on Beverly

In 1920,

there were no child-labor laws to protect teens like Beverly, and no safety

regulations or regulators like OSHA to ensure workplace safety. On March 11, 1920,

just two weeks after his marriage, Beverly suffered a horrific workplace

accident. As described in the news article below, Beverly was leaning into the

hogshead, which would have been about four feet high. He was probably adding

more tobacco to the barrel when the metal cover plate came loose and fell on

his head, crushing him between the plate and the rim of the hogshead. He was

knocked unconscious and “an examination showed that “part of his scalp was torn

off and his face badly bruised.” He was hospitalized in critical condition.

A very brief

article eight days later reported that he was “doing as well as could be

expected, and it is now thought that he will recover.” There was no mention of

the tobacco company doing anything to help him or to take responsibility for a

nearly fatal accident—no offers to pay the hospital expenses or to help his

young wife. Beverly probably lost his job due to his inability to come in to

work. The original news article reported he was 20 years old, not his actual

age of sixteen, so the company seems to have lied to the press or failed to

verify the age of new employees.

Beverly

suffered another blow in April of 1920, when his grandfather John Presley

Moseley died. Beverly had lived with his grandfather during part of his

childhood, so was likely close to him.

Beverly

had recovered enough to attend dinner at his brother-in-law’s house in May.

However, in June of 1920, he asked the court to appoint his grand uncle Charles

Jackson “C.J.” Moseley to be his guardian. His motion was granted on June 12,

1920. Why would he do that? Was his head injury so serious that he couldn’t

handle his own affairs? Or was it simply a more practical matter—he was too

young to sign most legal documents like leases or loan documents, so his uncle

could handle that for him? Of course, this begs the question as to why he turned

to his great uncle—why didn’t ask his father to help him? Was he estranged from

his father and siblings, who lived nearby?

Despite

these difficult early years, Beverly was able to build a decent life. He and

his young wife Lucy became parents before the year was out, and went on to have

three more children. Sadly, the marriage did not survive; Beverly and Lucy separated

sometime in the 1930s and divorced in the 1940s. By the 1940 census, Beverly

was living in Owensboro; two of his children, Dale and Lena, were living with

him. Beverly remarried in 1946 to Johnnie Westerfield.

Beverly

changed careers after his accident at the tobacco factory. He got a job with an

Owensboro company, Barrett-Fisher, that made saddles, harnesses and other horse

equipment. Beverly became a harnessmaker, and according to his obituary, he made

harnesses for 44 years.

Beverly

died April 27, 1969 in Owensboro after a “brief illness”. He was sixty-five

years old. Beverly is buried in the Rosehill Elmswood Cemetery.

|

| Photo by Charles and Monta Vanover on Findagrave. |

Beverly

Childress had some hard times when he was very young, but he overcame them to build

a decent life for himself and his family. Hard times may leave scars, as I’m

sure Beverly’s accident did, but they don’t have to define a life.

Sources:

Information

on prizing tobacco and hogsheads. “Analyzing an Artifact: What in the World is

a Hogshead?” by Alison Holcomb. Tar Heel Junior Historian. Spring 2009. NC

Museum of History. https://www.ncpedia.org/tobacco/barrels

Item on

Childress recovery. Item on Dinner with A.J. Kirk and Wife. Hartford Republican.

19 Mar 1920 and May 7, 1920..

Article on

Beverly Childress Injury. Court Notice of Guardianship. Owensboro Messenger.

Owensboro KY. March 11, 1920, June 11, 1920 issues.

Obituary. Owensboro

Messenger Inquirer. April 28, 1969.